Reverb Effect – what is it and how does it work

Everything you will ever need to know about the reverb effect, how it works, when to use it and how to use it

Effects

Reverb Effect – what is it and how does it work video tutorial delves in detail how a reverb effect works and how to use it.

Reverb serves a number of purposes and the two most important ones are that of ‘colour’ and ‘space’. It can also be used as a corrective tool, for example: helping to add tails to sounds that have been cut abruptly. The reverb effect – what is it and how does it work video shows how important reverb is to the producer. Itis the most used effect of all in music production and rightly so. It now only adds colour and depth to a sound, it defines the space that sounds will reside in within the mix.

The type of reverb used is as important as how to use it. There are occasions whereby a certain type of reverb is required on a specific sound or mix because of its design and build: a plate reverb used on vocals is a good example.

We have been listening to music acoustically, for thousands of years. The natural acoustical space that the music was played in determined how the music was perceived. The environment and the materials that made up the surrounding environment had a huge impact on how the music was ‘heard’. We may think that we are the innovators when it comes to creating the right ‘space’ for music to be heard in but the Romans and Greeks had a head start on us and designed their amphitheatres and arenas to do exactly this. Some of their designs are truly impressive. Their understanding of space and the materials the space was constructed from is remarkable even today.

So, how does reverb work?

The listener hears the original sound, plus all the reflected sounds that come from the original sound reflecting off surfaces within the environment. These reflections are reflecting at varying distances and times. This is the nature of how sound moves in a given environment. As a result, the listener hears a composite of the original audio signal, the first reflections, and the delayed reflections.

These ‘signals’ will eventually lose their energy and dissipate.

Imagine a square room whereby you, the listener, are sitting in the middle of the room. For now, let us work under the premise that the sound that emanates from you emanates in all directions as opposed to being directional (which sound is). The room is made of brick walls coated with plaster. The walls and ceiling will have reflective properties. You shout. The shout begins to reflect from the nearest surface and ensuing reflections come from different angles at different times from different parts of the room. This makes perfect sense as the further away a reflective surface is the longer it takes the sound to reach it and reflect. The trajectory of the reflection depends on the angle the sound reaches the surface and the angle the surface is at, for example, a sound reaching one of the corners of the room at a 90-degree angle will reflect at that angle and reflect off another surface and continue to reflect until it dissipates or loses energy. A good way to imagine the reverb aspect is to think like this: after you have shouted the residual sound that remains is the reverb. You can imagine what this means in rooms that have reflective surfaces, absorbing surfaces, irregular shapes and so on. High frequencies are more prone to absorption and rooms with absorbing material (curtains, carpets etc.) will sound more muffled. Rooms with hard reflective surfaces will sound brighter and more brittle.

So, reverb is simply a term that defines the reflective properties of a given space and how those reflections are projected and processed.

Today, we emulate the space of the environment and use this in our music.

Our effects units can not only emulate real spaces but also create spaces that do not exist naturally in nature like gated reverbs or reverse reverbs.

Figure 1 is a simple diagram displaying the various features of how reverb behaves. The terminology used has stayed the same for a long time although new features and therefore terminology has been introduced in modern-day VST effects.

Fig 1

When the sound is triggered there is a pre delay just before the signal reflects off the first surface. The time taken for the signal to reach and reflect from the first surface is known as ‘pre delay’. In other words, the pre delay controls the amount of time taken before the reverb sound begins. By adjusting this parameter you can impress a change in distance. The longer it takes for a sound to reach a reflecting surface, the further that reflective surface is away from the sound source. This is the first stage in the reverb process.

This is then followed by the early reflections. The early reflections are the primary reflections after the pre-delay and this is actually quite significant as it will denote the shape and size of the room before the decay sets in which in itself further defines the dimensions of the space. We tend to concentrate more on the pre-delay and the early reflections to reference ourselves to our surroundings/environment than we do to the dissipation process of the ensuing reflections. The decay time (also known as reverb time) denotes how long it takes for the reverb sound to dissipate/lose energy, or die. The decay itself is equally important when gauging the surface absorption properties of the space. We can control the texture, length and behaviour of the decay in such a way as to create a new colour or to expose the surface material. In most reverb units you will have a high-frequency roll-off, sometimes referred to as HF damp. In natural spaces, high frequencies dissipate quicker than low frequencies. By controlling this roll-off we can simulate the frequency dissipation. However, we can also manipulate this by using traditional filters post reverb. The depth and detail of control over these features allow us huge flexibility and scope to create interesting environments and textures/colours.

As the image in Fig 1 shows, there are a number of early reflections spaced out between each other. This is where diffusion comes into the equation. Diffusion parameters control the spacing in between the early reflections. The tighter they are packed together, the thicker the sound, and vice versa. The more diffusion you apply the thicker the reverb will sound. This can translate across as ‘dark’ or ‘confined’. If you apply less diffusion, the opposite happens; you space out the reflections further apart and make for a thinner reverb sound.

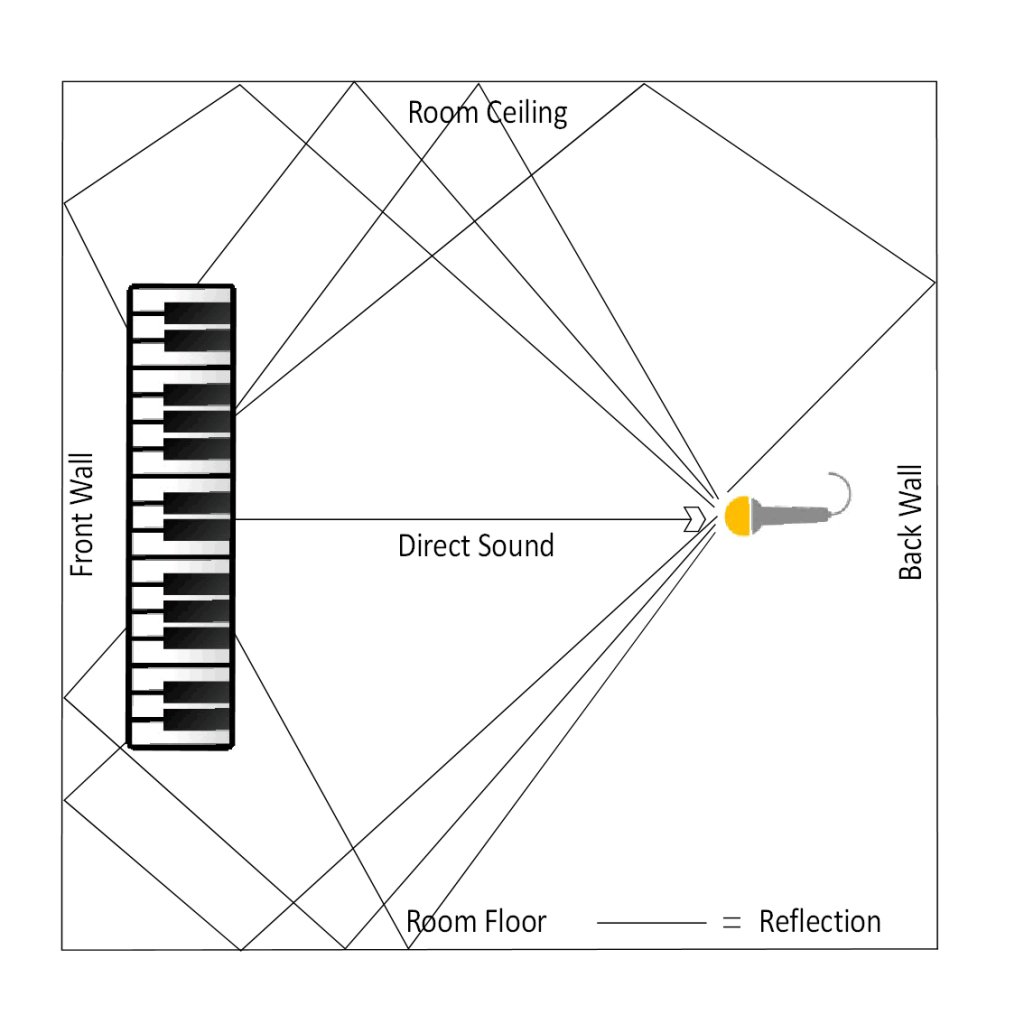

Figure 2 shows how sound is reflected in a room.

The direct sound is the sound that comes out of the keyboard and goes directly into the microphone without reflecting off any surfaces. The black lines represent the reflections. They are going and coming from all angles and the microphone records not only the direct sound but all the reflections as well. Of course, I have only drawn a few reflection examples but you can appreciate what happens when you have countless reflections coming from all angles at different times.

Sound travels at approximately 1130 feet per second which equates to about a foot per millisecond (ms). Using the example of the room reflections it is easy to see that some sound waves will travel further than others some will travel shorter distances and others will bounce around the room. Because the speed of sound is constant it then follows that the sound waves will all arrive at the listening or recording position at different times. The bigger the space the longer it takes for the sound to reflect and arrive at the listener/recording position. This time factor denotes the size of the space. Add to that the dissipation time, the time it takes for the sound and reflections to lose energy, and you have further information about the size and characteristics of the space.

Fig 2

Working from the image we can now ascertain a few bits of important information:

The direct sound is the ‘dry’ sound that comes directly from the sound source without any colouration whatsoever. The reflections are referred to as ‘wet’. In fact, this word is applied to any effect that is separate from the dry signal/sound source. This term denotes how much of an effect we want to apply to the dry sound. I am sure you have come across this on many effects VSTs. The dry/wet knob/fader (also called ‘mix) is used to mix the dry signal with the wet (effect) signal. In the image, the microphone is picking up both the dry signal and the reflections (wet signals) and the combination of the two is referred to as the ‘mix’. By using the wet/mix control we can have further control over space and density. Reflections from different angles arrive at different times and this can further determine the characteristics of the space occupied. It is normal for higher frequencies to dissipate quicker than lower frequencies in a given space and this piece of information can go a long way in not only determining the shape and reflective surfaces of the space but also when we want to sculpt the reverb for coloured use. It is not uncommon to use a high pass filter post reverb to remove unwanted lower frequencies and vice versa. In fact, most of today’s VSTs have some form of EQ/filtering built within the VST. When dealing with low frequency sounds it can sometimes be a nightmare taming the reverb as reverb can sound like mush and it is here where a combination of dry/wet and filtering processes can be a real help. If reverb is applied incorrectly to low-frequency sounds then the definition is compromised. But this doesn’t mean that high-frequency sounds don’t suffer either. When using reverb on high frequency sounds the actual reverb effect can sound considerably more pronounced and it is here where, apart from using the usual parameter controls, filtering can be your best friend. Generally, I tend to try to limit reverb use on low end sounds like basses or kicks and if I have to use reverb then I will almost always filter the lower frequencies out. And when dealing with high frequency sounds the HF roll-off is my ‘go to’ parameter. The shape of the space is critical when determining the colour and character of the reverb being applied. In large spaces, the echoes can be further controlled so as to provide a sense of direction and shape. In smaller spaces, this is less pronounced but equally important. When you shout in an irregular large space you will often hear some of the reflections as distinct separate sounds emanating from different directions. This is down to the angles and time taken for the reflections to arrive. Caves and mountains are good examples of delayed sound emanating from different directions. This example may seem a little ‘out there’ but it is critical for a producer or sound designer to understand direction and space. When dealing with sound effects for film this becomes even more important. However, as an example, it serves us well to understand distance and position. A number of VSTs nowadays exhibit a multitude of presets that have different shape characteristics with the added advantage of allowing the user to reshape any space both in terms of angles and size. The position of the microphone is crucial when recording a sound. The image shows the microphone in a central and equidistant position. This means, if the room is shaped symmetrically as in our example, all the reflected sounds will arrive equally at the same destination at the predetermined times and angles. This means there is no bias to either side, and the source sound is perceived to be dead centre. If the microphone is moved a little to either side then the times and angles of the reflections will also change. This will then denote a change in position. You may be wondering why this is important when dealing with reverb. Well, it allows us to understand where a reflective surface is and how we can utilise that to express our sound. It also serves as a great way to ‘move’ the perceived space of a sound simply by panning the reflections. Early reflections are probably the most important factor when dealing with a given space as they will be more pronounced than the ensuing reflections. The early reflections will give us enough information so as to be able to denote direction (and therefore proximity/distance) and also a little information about the reflective surfaces. The initial reflection will be the pre-delay and the immediate ensuing reflections will be the early reflections. A combination of both gives us the necessary information we require to understand the characteristics of the space. The ensuing and complex reflections are harder to decipher but no less important than the pre-delay and early reflections. Nowadays, vsts will afford control not only over the pre-delay (standard on almost all units) but also the early reflections and how they are structured.

In the Reverb Effect – what is it and how does it work video I run a vocal take through two different reverb plugins. I explain how reverb works and demonstrate to you how the various reverb parameters affect the sound’s overall texture. I explain how iZotope Ozone Reverb and Toneboosters TB Reverb work and how best to use them to process female vocals. I show you what the best settings are to use in achieving different reverb textures.